“Truman Capote, an Interview,” by Cathleen Medwick, was originally published in the December 1979 issue of Vogue.

For more of the best from Vogue’s archive, sign up for our Nostalgia newsletter here.

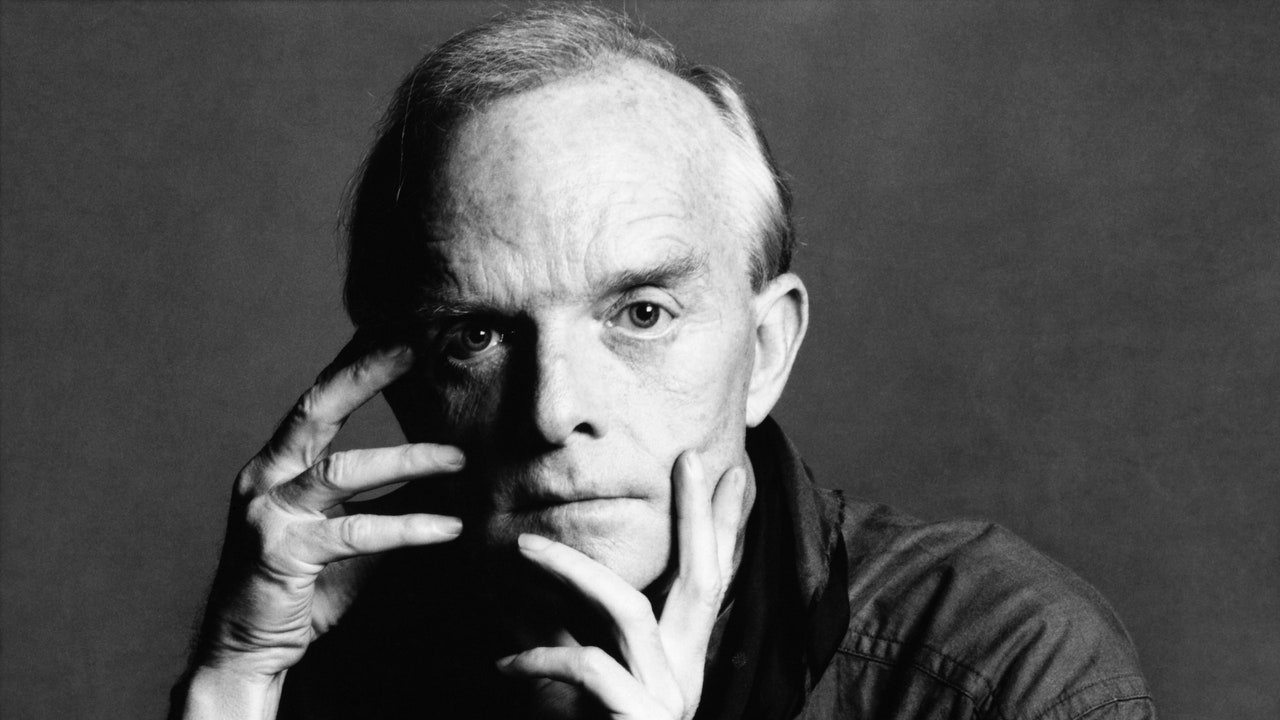

Truman Capote knows how to make an entrance. He has always known. In 1948, when he published his first book—a slim siren of a novel called Other Voices, Other Rooms—he quite simply created a sensation. It was not just the lush beauty of his prose, his precocious mastery. It was also that the book’s jacket displayed a photograph of the unknown young author: a delicately pale young man reclining on a chaise lounge, his eyes leveled provocatively at the camera. They were the eyes of a lover, or a murderer. A tough faun, as a friend has said. Truman Capote at twenty-three was the New Orleans country boy who came to the big city and, with cool country know-how, seduced it. That was an artful seduction: as though Truman, a boy fishing at an enormous pond, spotted a great, elusive fish and knew just how to get it: camouflaged his hook with gleaming bait (himself) and waited with the patience of saints. When he caught that fish, fame, he caught it suddenly, and for keeps. His talent, was, of course, the hook. Without that, he could never have joined the front ranks of contemporary Southern writers—Porter, Welty, McCullers— and stayed there, as one of America’s foremost literary talents, for over thirty years.

Since the boy on the book jacket, we have seen many Capotes. Like a wizard, he is always assuming new shapes, new disguises. A small, dapper Capote in a grey pinstripe suit and black-rimmed glasses, leading a gelatinous Marilyn Monroe in a dance at El Morocco in 1954. A beaming, black-tie Capote in a black mask (Capote the social butterfly), the darling of the jet set, ushering newspaper heiress Katharine Graham into the $75,000 ball he threw for her in 1966—threw it, he said then, in order to go to a party where he could really have a good time. A thinner, dowdier Capote (one of his friends said that his pants always looked baggy, like he’d been whacked in the ass with a shovel) being frisked at San Quentin, where he was interviewing murderers in 1972—several years after his mercilessly detailed account of a Kansas murder, In Cold Blood, established him as a major force in American writing (Capote the serious author). A plump, porcine Capote wearing shades and playing in the 1976 movie Murder by Death (Capote the movie star). A betrayed and belligerent Capote, after chapters from his still forthcoming book Answered Prayers, a thinly disguised tale about his jet-set friends, were published in Esquire, and the Beautiful People closed their doors on him. Finally (it seemed then), a down-and-out Capote confessing his addictions to drugs and drink on the Stanley Siegel talk show, and expressing quivery intentions of overcoming his addictions—if he didn’t accidentally kill himself first.

These were the images the press eagerly fed the public over the years. Or, rather, the images that Capote fed the press. But no matter how many masks he assumed, how much each new Capote shocked and titillated the public, there was always a backbone of achievement that made Capote more than fodder for gossip columnists, or his erstwhile friends. There was always a new work, and it was always good. Capote’s writing, like his public image, seemed capable of endless transformations. Out of the haunting prose-style of The Grass Harp and the early stories he distilled a new literary genre—a kind of reporting that revealed reality to be even more freakish, more fabulous than fiction. In Cold Blood was (like its author) vivid, shocking, and impossible to ignore. As Capote’s own life became more of a fable than ever, as the “tiny terror” sharpened his claws on Gore Vidal and other opponents, as his social status plummeted, the public’s appetite for Capote’s prose became even keener. Today, more than ten years after it was first promised to them, prospective readers of Answered Prayers are still licking their chops with anticipation. Fame and notoriety have always mirrored each other in Capote’s life, and still do, like the Siamese twins he uses nowadays as his literary personae: Capote, meet Capote. Janus faces, the killer and the saint.

#Archives #Honest #Interview #Truman #Capote