This story originally ran on Fashionista in 2017.

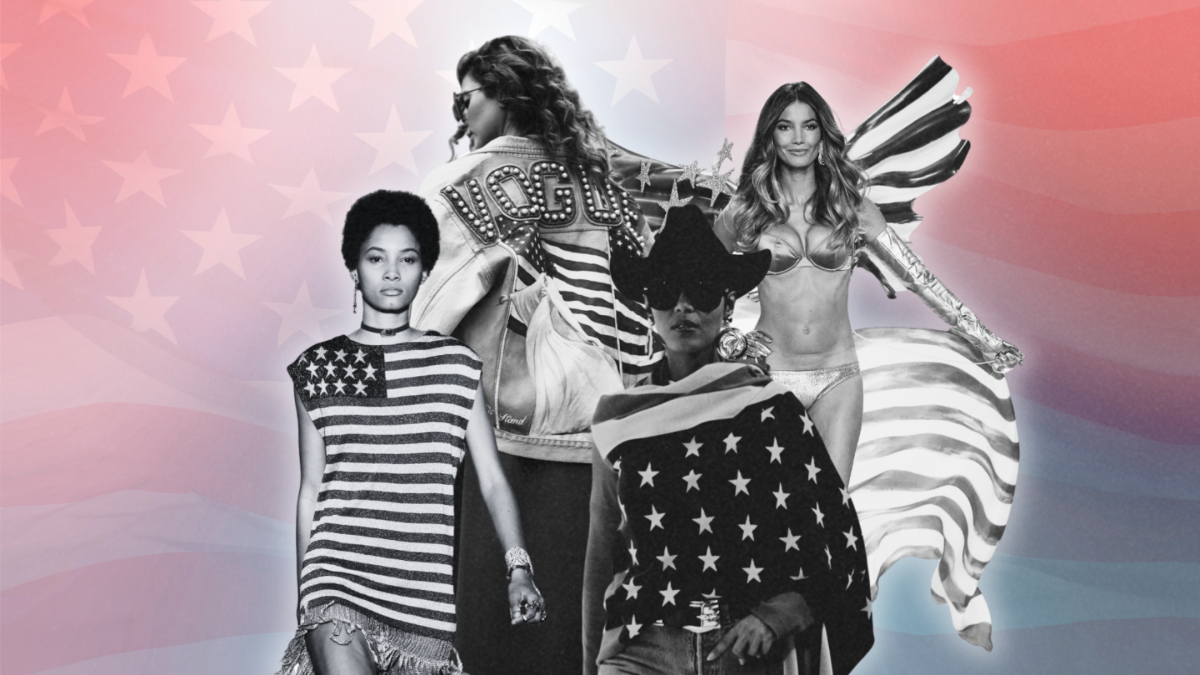

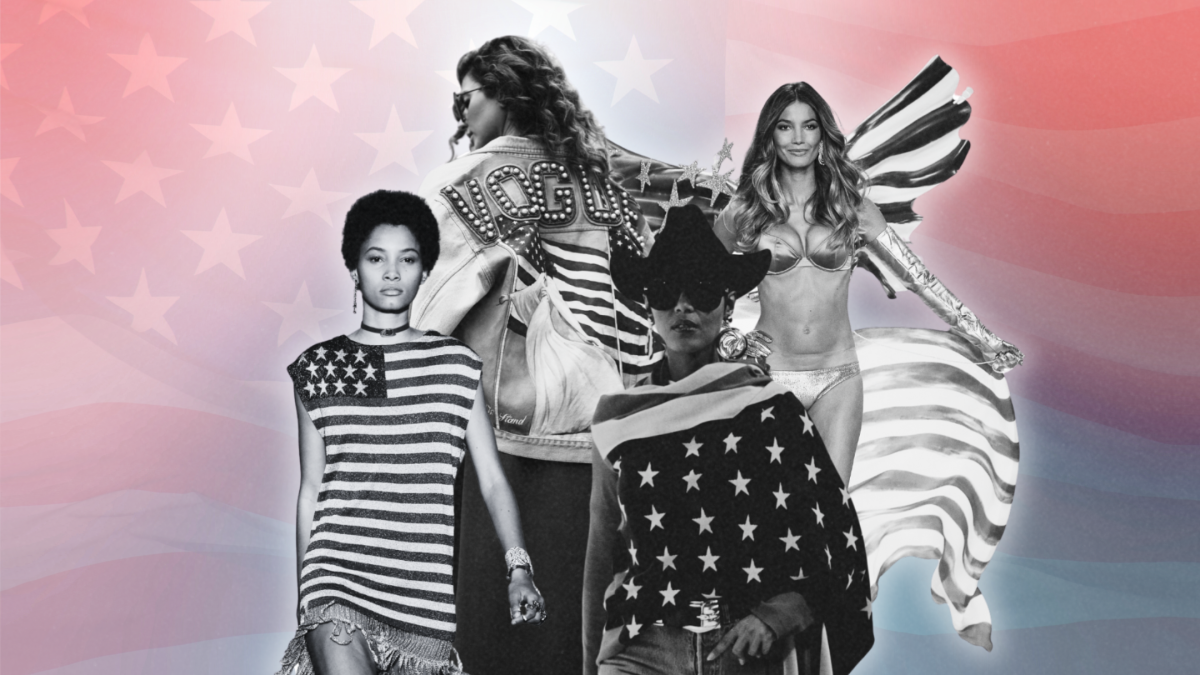

There’s a certain prestige that comes with fashion that is “Made in the U.S.A.”, and marketing departments obviously know that the designation has yuuuuge selling power. The ubiquity of fashion brands touting their allegiance to American manufacturing seems oddly similar to brands that celebrate their dedication to sustainability. After all, the coveted distinction of being “sustainable” or “made in America” is an effective way to create a do-good, feel-good image for a brand, differentiating it from other companies that lack any outward social purpose. While this marketing-savvy concept may seem most relevant to the age of globalization and mass-manufacturing, the importance of supporting American-made fashion in fact dates back to our country’s fight for independence against the British. But does this designation really signify patriotism, or is it just a longstanding marketing trend?

Historically speaking, Americans become more aware of their purchasing choices during times of political unrest, as consumption can serve as an easy way to actively demonstrate political ideology or support for a cause. [3] This was especially important during World War II, although the sentiment remains relevant in our current, uh, not-so-stable political climate. In order to better understand the true meaning behind the desire to be labeled “Made in the U.S.A.” today, we’re taking a look back at how the notion itself has affected popular fashion throughout the nation’s history, from the onset of the Revolutionary War to the untimely demise of American Apparel.

THE HOMESPUN MOVEMENT AND REVOLUTIONARY WAR

Fashion played an important role in the early days of U.S. history as citizens had to decide what it meant to dress like an “American” while the nation was still building itself from the ground up. The need to distinguish America as a strong political and economic presence, not reliant on manufacturing from other countries, led to politically based promotion that encouraged consumers to purchase American-made goods. (Sound familiar?) U.S. citizens produced their own clothing in order to demonstrate their newfound independence and to become more unified as a nation, making it much more than just a means for selling American-made goods. [1]

During this time, it wasn’t enough for a garment to just be constructed in the U.S.A.: The Homespun Movement encouraged patriotic women to make their own yarn, textiles and clothing, giving all aspects of fashion great importance. Consumption of domestic goods became a method of resistance against British taxation and oppression. Most importantly, embracing fashion that was “Made in the U.S.A.” (even before the phrase was used) gave women a chance to participate in the fight for independence without having to leave the comfort of their domestic sewing circle.

THE “AMERICAN LOOK” AND WORLD WAR II

World War II was a turning point for American fashion, as it would be the time when stateside fashion designers had to step up and break free from the style “dictators” that ruled the fashion world from across the Atlantic. Of course, this was somewhat necessary since Paris — the uncontested style capital of the world — remained occupied by the Germans throughout most of World War II, forcing the American fashion industry to focus on its own design talent. Regardless of the circumstances, purchasing fashion that was designed and made in the U.S.A. became symbolic of national pride and civic service.

The tense and uncertain political climate of the World War II era triggered an outpouring of political messages from the government, encouraging citizens to support the nation’s war effort by purchasing American-made goods. No longer just considered a shallow and meaningless practice, purchasing American-made fashion designs served as an accessible form of political participation for the American people, which allowed them to feel more connected to the war effort. Clothing’s ability to carry personal and political messages was once again seen as a way to unify the nation, and the “Made in the U.S.A.” label was a powerful way to promote feelings of patriotism and allegiance through consumer culture. [2]

Although it began to be recognized in the 1930s, the 1940s were truly the formative years of the “American look,” a distinctly casual and functional form of style that has been the hallmark of American fashion ever since. However, fashion historian Valerie Steele notes that during the 1940s, “the term American Look functioned primarily as a promotional tool that sold clothes by generating pride in American-made goods.” [4]

Nevertheless, the positive effects generated by this use of marketing should not be underestimated: Adopting the so-called “American Look” and consuming American-made goods was a powerful way for U.S. citizens to identity themselves in troubled times. During a period when the American population was faced with extreme circumstances that threatened the way they lived, such promotion turned the struggle into a positive movement that was worthy of pride and excitement rather than panic and grievance. Whether or not this sort of effect would be possible to achieve today is difficult to determine based on how interconnected our world has become.

NEW REASONS TO BUY AMERICAN-MADE GOODS

In a time when the majority of U.S. clothing manufacturing is outsourced and overseas labor tragedies seem far too common, many consumers take comfort in the idea that an American-made good was (hopefully) created under better conditions and higher standards, bringing another meaning to “Made in U.S.A.” Case in point: American Apparel found success by building a brand around the idea of eliminating the perceived mystery of where our clothes actually come from. Founded in 1989, the brand kept production within Los Angeles while selling to a mass market through vertical integration. While their labor practices (and CEO) were certainly not free of controversy over the years, it’s obvious that American Apparel benefited from the altruistic notion that comes with purchasing clothes that are made on domestic soil.

The “Made in the U.S.A.” concept acquired a new meaning after the financial crisis of 2008, as it became a sartorial status symbol in American menswear, which stemmed from a consumer interest in buying high-quality, long-lasting goods. In the mindset of helping the economy and saving money (in the long run, of course), being “Made in the U.S.A.” signified high style and ruggedness along with warm, fuzzy feelings of patriotism. Both newly established American-made brands and companies with long-standing traditions of keeping domestic production found hoards of new customers in the late aughts. This was especially connected to a sartorial trend towards “American heritage” styles, such as Pendleton sweaters and Red Wing boots.

Of course, times are changing, and the meaning behind “Made in the U.S.A.” has recently acquired some undesirable connotations as well. The movement was once about “celebrating craft and investing in quality, lasting garments, while also helping to revitalize a dying industry,” menswear writer Brad Bennett told the New York Times. However, now that our current president has used the phrase repeatedly to rally his supporters, some argue that it’s become associated with Trump’s own ideology instead of being seen as a concept that’s free of political biases.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TODAY?

Considering the fact that it has centuries of political meaning imbued in it, the “Made in the U.S.A.” tag is actually much more than a modern marketing gimmick. The concept of high quality, American-made fashion and the democratic ideals that it represents can help to create a sense of singular identity for a nation that’s home to millions of diverse citizens. Additionally, as a relatively young country that fought for its independence in the not-too-distant past, the choice to purchase American-made fashion continues to serve as a way for U.S. citizens to demonstrate their sense of freedom and celebrate what the founding fathers hoped to achieve.

However, some economists and business owners have argued that there really is no such thing as being completely American-made in the era of global supply chains, making the meaning behind “Made in the U.S.A.” continually in flux. While you can easily purchase a pair of bespoke jeans constructed in Brooklyn, there’s a good possibility that the necessary materials, from dyes to hardware, came from factories overseas. Evidently the concept of being “Made in the U.S.A.” is complicated and often reliant on workers that come from around the world, much like the country itself. That being said, we’re proud supporters of American-made brands, and whether it be your own backyard or a factory in Vietnam, it’s better to know where your clothing was made and, ideally, more about the people who made it.

Sources not linked:

[1] Haulman, Kate. The Politics of Fashion in Eighteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

[2] Lipovetsky, Gilles. The Empire of Fashion: Dressing Modern Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

[3] Parkins, Wendy, ed. Dress, Gender, Citizenship: Fashioning the Body Politic. Oxford: Berg, 2002.

[4] Steele, Valerie. Introduction to Claire McCardell: Redefining Modernism, edited by Kohle Yohannan and Nancy Wolf. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1998.

#Fashion #History #Lesson #Evolution #American #Clothing #Manufacturing